Annual clovers are a core base for many pasture paddocks in South Australia. Unfortunately, oestrogenic clover varieties (i.e., Yarloop, Dinninup, Dwalganup and Geraldton) have a long history in the higher rainfall areas, contributing to significant impacts on lambing percentages. Yarloop was sown in pastures (as part of the WW2 Soldier Settlement Scheme), and Dinninup was introduced as a contaminant of certified Mt Barker in the early days.

Over the years, there has been a shift in the oestrogenic clover varieties dominating pastures, with Dinninup and Dwalganup being more prevalent than Yarloop now. Whilst many pastures have been renovated and newer non oestrogenic clovers introduced there is evidence that high levels of oestrogenic clovers still exist in some pastures. These clovers are still contributing to high numbers of dry ewes and reduced lambing percentages on some properties. Albeit, not as severe as seen in the 1960’s, however still significant enough to impact on productivity and profitability. When these clovers make up 20 percent of the pasture eaten by ewes ‘clover disease’ or ewe fertility problems could occur.

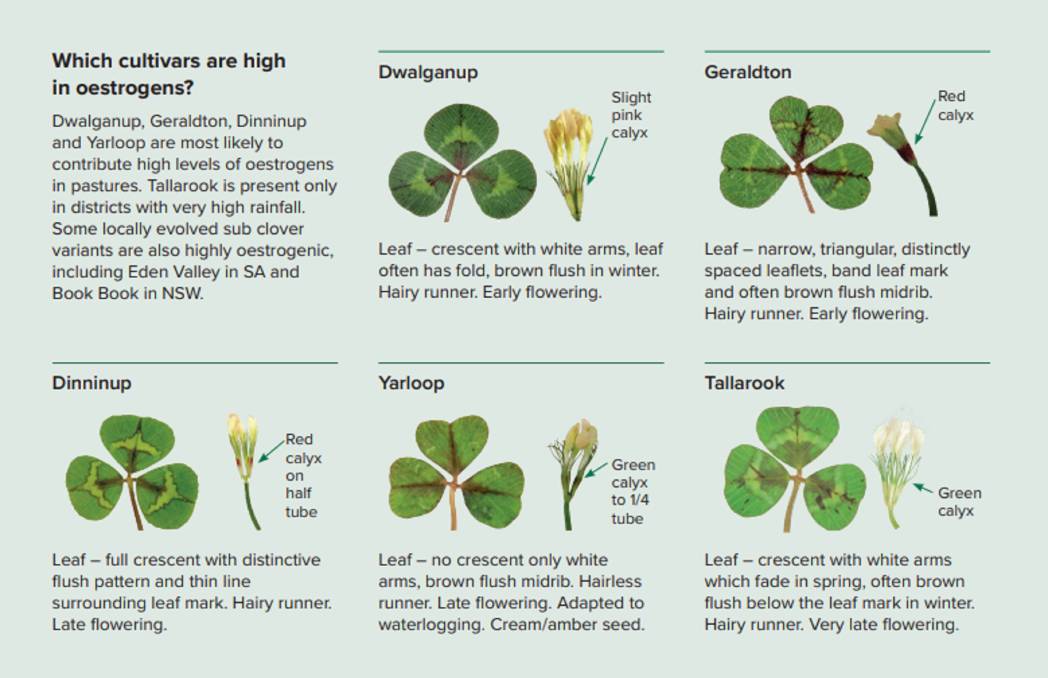

As spring progresses the clovers will start flowering. This is the best time to identify the clovers. Identification of subterranean clovers is simplified by assessing three sections of the plants: the leaf markings, the hairiness of the runner, and the colour of the flower calyx. See Figure 1 or refer to the ‘Good clover, bad clover—identification’ fact sheet.

Figure 1 : Oestrogenic clover identification

(Source: UWA)

Once oestrogenic cultivars have been identified the next step is to determine how potent the pasture may be to sheep. This will vary with the botanical composition of the pasture across the paddock. Other good cultivars low in oestrogen and other pasture grasses and broadleaf plants will collectively dilute the amount of oestrogens that the sheep will consume.

Paddocks can be assessed by one of two methods— visually by the ‘stick method’ or by collecting clover samples and sending them for laboratory analysis of oestrogen levels. For further details on paddock assessment refer to ‘Good Clover, Bad Clover’ factsheet.

The good news is, if oestrogenic clovers are found, there are management strategies available to producers, which include:

1. Understand the issue

2. Graze strategically

3. Manage pastures